The Delta Issue #66

Systems, Not Slogans: Real Change Requires Relentless Implementation

Hi y’all, Jessica here.

Every year, The Thomas B. Fordham Institute hosts a Wonkathon, a friendly competition for big ideas in education.

This year’s Wonkathon asked a great question: What needs to happen next—at the state, district, and school levels—for the science of reading revolution to fulfill its promise and ensure that far more children learn to read well?

Kunjan Narechania and I have lived this work with states, so of course, we had to respond.

Our piece is called Systems, Not Slogans: Real Change Requires Relentless Implementation. The title says it all. If we want kids to read, every adult—from the statehouse to the teacher—knows their role, gets real support, and has the tools to do the work.

Here’s the full piece below. Give it a read, check out the resource we included, and maybe cast a vote for us while you’re there!

🗳️ Vote for team Watershed Advisors through the online survey.

Look closely at Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, and DC, and you’ll see that the places getting reading right are the ones getting implementation right.

What’s driving the “Southern surge” is not one initiative or even a series of initiatives aimed at fixing the reading crisis, it’s that these states have built a system that drives a relentless focus on implementing the policies they pass.

People often hear the Mississippi story and say things like, “They had literacy coaches. That means we need literacy coaches and we’ll get our kids reading.” But that’s like watching professional basketball and assuming that if you had the same uniform, you could play the same game. It’s not just the uniforms, and it’s not just the literacy coaches. It’s the coordination among the players driving to one goal—the system they’ve built as a team, with all the moving pieces moving in the same direction—that helps them win.

In order for more states to get literacy right, they need to restructure their education agencies around a limited set of goals and reorient their entire system to drive toward those goals. It will mean making hard decisions not just about what to start doing, but also about what to stop doing.

In our experience, effective systems are made up of these four components:

- A coherent vision for an improved student experience shared among everyone in the state, along with rigorous standards that are aligned with that vision and make sense in the lives of kids and teachers.

- An implementation chain that names every player between the statehouse and the student, describes the most important adult behavior shifts they must make to achieve the student vision, and includes a plan for measuring the extent of these changes.

- A plan for using the state’s most important levers, including standards & assessments, funding, accountability, regulations & guidance, support & training, and communications, to elicit behavioral shifts from everyone in the implementation chain.

- Implementation data that drives improvement, specifically data about whether educators are actually changing how they do their daily work that can help shape adjustments to overall strategy.

Without this level and depth of system reorientation, we end up with states saying, “We passed science of reading policies, not sure if it’s working, but hopefully scores go up next spring.” If we want results for kids, the entire system — from the academic team, to the multilingual learners’ office, to the special ed department, to principal, teachers, and coaches — needs to move to one goal and measure progress every step of the way.

Coherent Vision

The vision has to start at the classroom level: What do you want the experience to look like for a third grader sitting at a desk?

During our tenure at the Louisiana Department of Education, our goal was to ensure all students were growing their skills and knowledge as measured by our state test. But that vision wasn’t specific enough to orient our entire system around it. We had to get even more granular to arrive at a goal that was hyperspecific and observable.

Here’s what we used instead: “In all 3rd-8th grade classrooms, students will read complex, grade-level texts that build their knowledge of the world. They will express their ideas about those texts through writing and speaking, while teachers facilitate student learning to deepen comprehension rather than focus on isolated reading skills.”

Too often states start their vision at the statehouse or only articulate their vision in terms of percent of kids achieving proficiency, when they actually need to start at the classroom level and ripple up through the system from there.

Implementation Chain

Implementing a new policy is like playing a high-stakes game of telephone with thousands of participants, where each person has to hear the message and do something new.

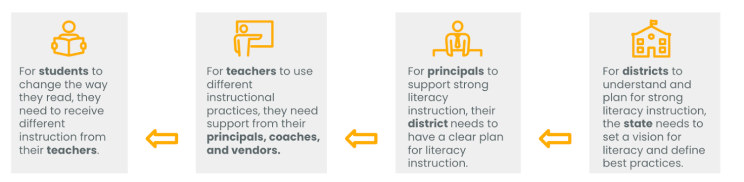

In any given state, there might be 50,000 teachers; 10,000 principals; and 7,000 district leaders, and in order for kids to experience something different in classrooms, all of them have to reorient their day-to-day behavior to the vision. They need to be clear on their specific roles in pursuit of the literacy goals.

The “implementation chain” is a map of all the adults who influence what happens in classrooms, from teachers to coaches, principals, and district leaders, and the specific ways in which each of these adults needs to adjust their daily work so that students benefit from the policy’s intent.

As part of Louisiana’s literacy work, we identified not just what actions teachers needed to take, but also what supports they would need from all the other actors in the chain.

If we wanted teachers to plan and facilitate instruction using new materials, they needed professional learning, regular feedback from coaches, and planning tools to prepare units and lessons in collaboration with their peers. If we wanted principals to ensure teachers have skilled instructional coaches, they needed to set clear expectations, create time in the schedule for coaching, collect observation data to adjust their school’s approach, and so on.

Levers

Adding literacy onto a pile of pre-existing state priorities won’t help more kids read — the pile has to go. Eliminating priorities isn’t easy, but it is essential. As the saying goes, you can do anything but not everything. States must choose what they most want to accomplish, and align every lever — standards and assessments, funding, accountability structures, regulations, training, and communications — to achieve that vision. The goal is to make the right choice, the easy choice.

States that are serious about improving student outcomes should be asking themselves:

- How can every discretionary dollar in the agency be spent on supporting districts, principals, coaches to make the shifts in the implementation chain?

- What trainings do we have to stop doing versus start doing to support the implementation chain?

- What department-issued newsletters, guidance, and communications do we need to stop sending out because they create distraction?

- In what ways are all the offices in the SEA aligned to the implementation chain–not just the academics team, but also the team thinking about students with disabilities, multi-lingual learners, and school improvement?

Here is a downloadable template we created based on what worked in Louisiana. State leaders can take this and make it their own.

Measurement and Improvement

Last, but most certainly not least, the system only works if we have information about whether we’re getting results — not just in terms of student achievement but also whether the actors in the system are changing. No more crossing your fingers and hoping for the best in the spring.

While student assessments are undeniably important, they are too far downstream to be the primary measure of implementation. Instead of waiting for student test results, states should measure early and often — and not just from a distance at the capitol, but on the ground in schools.

Kunjan will never forget walking into a classroom at a school that had adopted a high-quality curriculum and seeing the new materials sitting in boxes against the wall, unopened. Sometimes, the difference between implementing a new curriculum and not implementing a new curriculum begins with throwing the old stuff in the dumpster and then regularly observing that the new materials are being used. A standardized test will never be able to tell you that.

Doing this work is not glamorous. It’s not flashy. But Louisiana proves that it works. Since 2013, Louisiana has had the second-highest increase in 4th grade reading (second only to Mississippi). Overall, the state is now 14th in the nation. That’s not because of an initiative, or even a series of initiatives. It’s because Louisiana built and managed a system focused on classroom-level change, made it really clear what every person needed to do, pulled every lever, and never stopped measuring and improving.